Fairy tales are, as A. Dworkins argues, “the primary information of the culture”; that is to say they delineate the values and ideals within society that impressionable children ought to aspire to. They depict good and evil in polarities, whereby readers are compelled into supporting the actions of the sacred princes and princesses. The effect of such stories, that are so deep-rooted within cultural traditions, can be argued as a projection of cultural misogyny and the root of the female acceptance to such misogyny. In order to assess such claims, the composition of traditional fairy tales must be analysed.

Fairy tales are, as A. Dworkins argues, “the primary information of the culture”; that is to say they delineate the values and ideals within society that impressionable children ought to aspire to. They depict good and evil in polarities, whereby readers are compelled into supporting the actions of the sacred princes and princesses. The effect of such stories, that are so deep-rooted within cultural traditions, can be argued as a projection of cultural misogyny and the root of the female acceptance to such misogyny. In order to assess such claims, the composition of traditional fairy tales must be analysed.

The obvious patriarchy displayed in fairy tales is explored in the typical female characters that constitute the traditional fairy tale.

The wicked witch, evil stepmother, or despotic queen all depict the corruption and related problems of female-power. These sources of evil are the only examples of females displaying any authority in classic fairy tales. This indoctrinates the reader with the idea that females who hold authority will abuse their unjust power into causing a cruel society. Furthermore, the destruction caused by the tyrants is directed to the princess of the story only. In Snow White, the queen illustrates her power through the use of a magic mirror. This denotes the idea that women gain power through imaginary systems; the evil witches are never powerful due to how wise they are (unlike their male equivalents). Instead, the authors of fairy tales present the idea that wicked witches (the most powerful female figures in fairy tales) gain their power through ways that do not exist in the real world. This imprints on the child audience the meaning that a woman’s power and goodness are mutually exclusive, nor can they reach statuses of authority in the real world. The fact that the wicked witch disrupts the princess in her journey of goodness implies the idea that women who gain power perform an act of self-destruction, as they hurt other females, thus scaring female audiences away from the desire to gain power. The act of females gaining power results in a punishment upon womankind.

The fairy godmother’s appearance in traditional fairy tales in less frequent and many traditional fairy tales have only woven her into their storylines recently. She is the next most powerful female figure in fairy tales, however her magical characteristics once more exemplify the absurdities in female authority. She is the captured princess’s escapism and projection of her ideal: she is a powerful female figure in the fairy tale, however her power is not real. The princess clings to the support of a fairy godmother, however she is aware that she requires a man to provide her with life-long protection, as the fairy godmother’s magic is not a viable, long-term solution. This inculcates the idea that females cannot be independent, nor dependent on another female, however must find the support of a man to provide lifelong security. The fairy godmother’s power is only used to promote the sexist ideas of the author: the power is used in order for the princess to complete her housework and to look more beautiful. In essence, the fairy godmother helps the princess to be passive for her prince.

The princesses of classical fairy tales are an ideal for a young girl to aspire to: they are the epitome of goodness. Firstly, their names divulge, rather unsubtly, the authors’ sexist intentions as a large proportion of the names are simply physical attributes, such as Snow White, ‘beauty’ from Beauty and the Beast and Sleeping ‘Beauty’. These are examples of princesses’ identities being solely their ‘beauty’, thus imprinting onto the young, impressionable audience that the ideal woman’s identity is only to be of beauty. Contrarily, the male equivalent (the prince) hides from any individuality across all fairy tales, as the name ‘Prince Charming’ is applied to every fairytale. The male name is an attribute to the power he holds (as prince) and his nature (charming). As this is universally applied to all fairytales, children learn that all men of power are ‘charming’, thus conditioning audiences into social hierarchical generalisations and sexist comparisons. The nature of the princesses is similar throughout fairy tales as all princesses adopt a naïve, unworldly persona, thus furthermore illustrating the principle that the female ideal is one of little knowledge, as to prevent themselves from reaching authority.

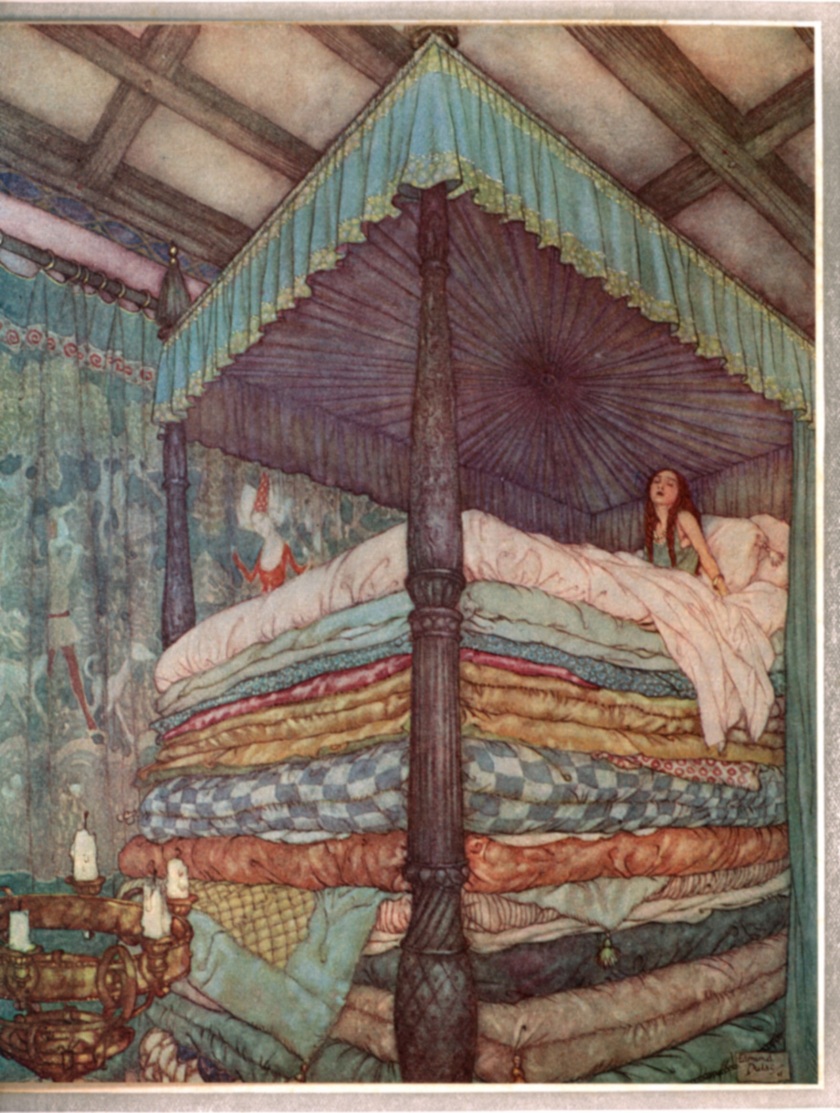

The disturbing treatment of the princess continues in the princesses’ journeys through the fairy tale; often their acts whereby they prove themselves as a princess involve violence. This notion indicates the passivity to violence that females ought to adopt, potentially leading to their passive responses to abuse, which are glamourised in fairy tales. The Princess and the Pea highlights this thought, as the princess must show her bruising after her night of sleeping under a pea. Only after experiencing this pain can the princess validate her status. Secondly, Sleeping Beauty pricks her finger, after being influenced by a wicked witch who is jealous of Sleeping Beauty’s power, causing her to fall into a deep sleep for one hundred years. The King attributes the biggest, most important room to his daughter, for her to sleep in; this implies the respect the males have for women who are passive, as Sleeping Beauty is completely torpid during her sleep. The princess is only awoken by the kiss of a prince. This idea proclaims that the utility of a woman is only actuated by a man. Following the kiss, Sleeping Beauty falls in love with the prince, implying that a woman ought to respect male attention, in spite of being raped.